The Wisconsin algorithm sheds another layer

Last night, I thought I’d finally solved Wisconsin’s Sum to One (S1) algorithm. Today, I know I didn’t. I have gotten closer, but not as close as I would like to be. This means I have to switch tasks for a little while, thanks to three other projects I am working on. Before I do, I just want to share the current state of this research and what it means in the context of election integrity.

The irony is that if the right solution is eventually applied, all of this research will have no further value. The voter rolls will be destroyed, and new voter rolls made from scratch. After that, no more algorithms to study (hooray!).

Current status S1 research

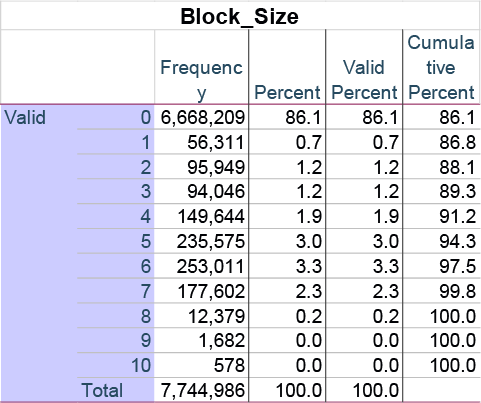

Wisconsin’s voter registration database contains approximately 7.7 million records. About 5.5 million records in the middle use the S1 algorithm. Each voter has two key numbers: a Voter ID (assigned when you register) and a ROW ID (a sorting index). The Row ID is the original sort order on data delivered by the Wisconsin Election Commission (WEC). If the data is sorted on any field after opening the database, the Row ID sort is permanently lost. The only way to preserve it is to 1) retain an original copy of the delivered file, or 2) create the row ID as soon as the file is opened, then resave.

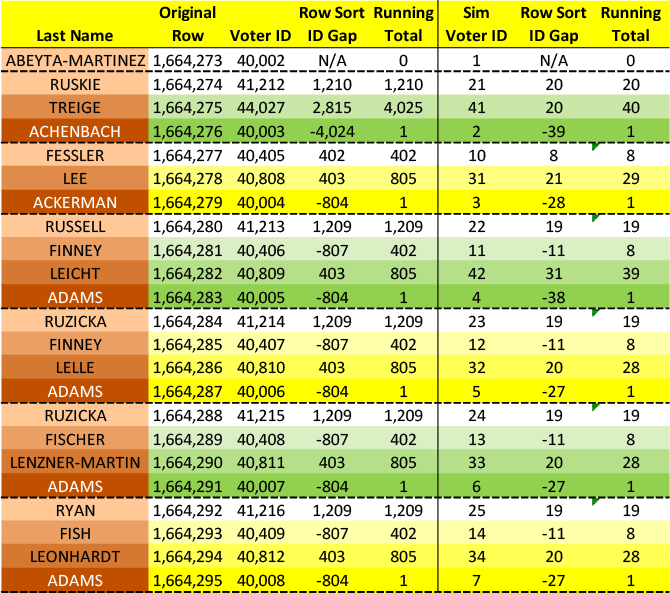

When I first looked at this data, I did a gap analysis. This involves calculating the numerical difference between adjacent numbers to see if they followed any unexpected rules. They did. I’ve already discussed this at length in other posts and my peer-reviewed paper. Here, I’ll focus on a simpler method of viewing the data that I’ve devised over the past few days.

When records are sorted by ROW ID, the gaps between consecutive VRNs follow a rule: they sum to exactly 1 within every 2-10 consecutive records. This creates natural “blocks” throughout the database.

This pattern holds across the entire 5.5 million records that use the S1 algorithm.

Why This Is Mathematically Significant

For VRN gaps to sum to 1 within a small block, negative gaps are mathematically required.

If you have 4 records in a block (3 gaps), and all gaps were positive, the minimum possible sum would be 3 (if each gap were +1). To achieve a sum of 1, at least one gap must be negative—meaning a record with a higher VRN must appear before a record with a lower VRN in the S1 sort order.

This is not how databases normally work. In standard practice, a sorting index either:

Preserves insertion order (VRNs would be sequential), or

Sorts by some attribute (alphabetical, geographic, etc.)

Neither produces the sum-to-1 pattern.

Empirical Verification

I tested whether the sum-to-1 property depends on the specific VRN values or only on their relative positions. Using the actual positional structure from the data but substituting arbitrary sequential numbers, the sum-to-1 property still held.

This demonstrates that the pattern is structural, not coincidental. The algorithm that created S1 ROW ID deliberately interleaves records from different VRN ranges to achieve this mathematical property.

Analysis of rank signatures within blocks reveals significant variety. While certain patterns dominate (4123, 4213, 4312 account for a substantial portion of 4-record blocks), hundreds of distinct permutations appear. This suggests the algorithm is more sophisticated than a simple “swap first/last” rule—it appears to select from multiple valid configurations while maintaining the S1 constraint.

Maintaining the S1 constraint across blocks requires awareness of neighboring values. For example, a block with ascending VRNs (rank signature 1234) can only satisfy the constraint if the previous block’s final VRN is greater than the current block’s first VRN. This inter-block dependency is inconsistent with standard sorting operations, which process records independently.

Algorithm Complexity

The permutation rules vary by block size. Blocks of 4-6 records follow a “swap first/last” pattern, while size-3 blocks use a left rotation. This size-dependent behavior is inconsistent with generic sorting artifacts, which apply uniform transformations regardless of group size. It suggests conditional logic—code that handles different cases differently.

What This Structure Does

Obscures registration order — The S1 sort order bears no obvious relationship to when voters registered.

Creates interdependence — Each record’s position depends on surrounding records. Adding, removing, or modifying a single record would break the sum-to-1 constraint for its block.

Resists standard auditing — Conventional database queries assume records are independent. This structure requires specialized knowledge to interpret correctly.

What Standard Database Practice Looks Like

Commercial database systems (Oracle, SQL Server, PostgreSQL) do not reorganize records to satisfy arbitrary mathematical constraints on unrelated fields. Standard indexing methods include:

B-trees (maintain sort order for fast lookup)

Hash indexes (distribute records for even access)

Clustered indexes (physically order by key)

None of these produce a “gaps sum to 1” signature. I am not aware of any documented database technique that does.

Claim

Regarding the S1 algorithm:

The structure exists and is mathematically verifiable

It does not match any standard database practice known to me

It has not been publicly documented or explained by Wisconsin election officials

It obscures the relationship between registration order and database order

The Question That Requires an Answer

Public voter rolls exist for transparency and auditability. A mathematical structure that:

Requires specialized knowledge to decode

Obscures chronological registration order

Does not match standard database practices

Has never been publicly explained

Can be used as a covert data channel

...raises legitimate questions about its purpose and origin.

I don’t know the answer to these questions, but they do deserve an official response.

Dates

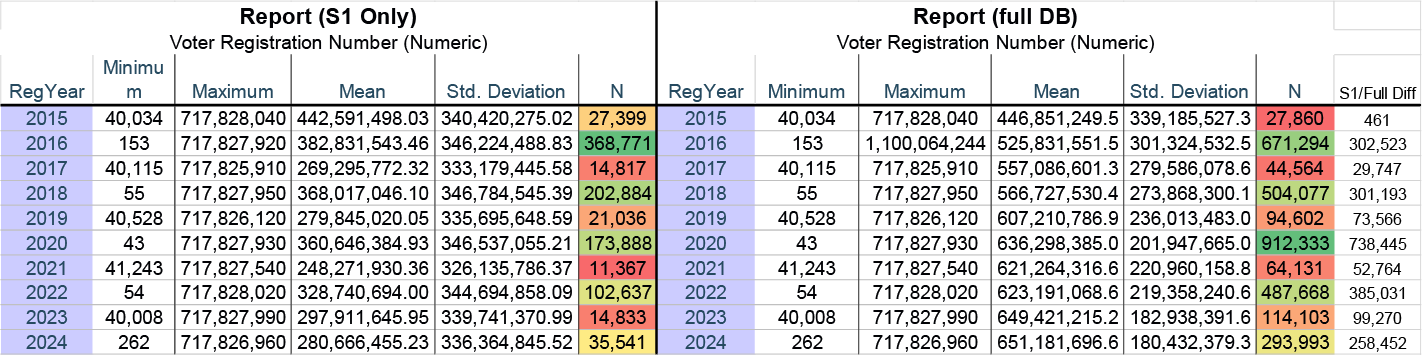

The S1 algorithm dominated Wisconsin’s voter registration database through 2015, when 98% of new registrations used S1. In 2016—the year Wisconsin joined the ERIC multi-state voter roll system—this dropped sharply to 55%. By 2024, only 12% of new registrations use S1.

However, S1 has not been discontinued. Hundreds of thousands of post-2016 records still use it, suggesting selective application of S1 to certain registrations.

A Final Concern

Since 2016, Wisconsin’s voter database has applied two different row-ordering methods to new registrations—S1 for some, a different pattern for others. Eight years later, 12-20% of annual registrations still receive S1 ordering. What determines which records get which treatment? The selection criteria has never been documented. A single database silently applying different algorithms to different voters, with no public explanation of why, is not transparency.

Notes (Provided by Sonnet 4.5)

Defensible claims:

The sum-to-1 pattern exists (empirically verifiable)

Negative gaps are mathematically required (provable)

The pattern is structural, not value-dependent (demonstrated via simulation)

This doesn’t match standard database indexing (verifiable by any database expert)

Claims to avoid:

“This proves fraud” (it doesn’t—it proves an unexplained structure)

“This is impossible without malicious intent” (unknown—could be an undocumented feature)

“The pattern is perfect” (The full ruleset that governs the S1 algorithm is unknown, though it can be described)

Impressive forensic work here. The inter-block dependency observation is especially sharp, basically showing that each block's validity requires knowing its neighbors' states. That kinda computational overhead doesn't appear by acident in production databases. Most indexing algos are deliberately stateless for exactly this reason, makes maintainance and scaling way simpler. The selective application post-2016 is the part that really needs official explanation tho.

Good analysis and crisply written with good support from AI.