The latest numbers are in...

Wisconsin is a very interesting state. Its voter rolls appear to have as many “errors” as New York’s, and possibly more on a per capita basis. These two states have what could objectively be described as the worst managed voter rolls in the country.

However, that is based on a sample of 15 states that doesn’t include California, Michigan or Minnesota.

Regardless, Wisconsin is interesting. Here are a few reasons:

They charge $12,500 for a copy of their state voter roll database. most states are free. Why the high price? Are they trying to avoid scrutiny?

A fascinating complex ID number-related algorithm. I call it the “S1 algo” short for “Sum to One”. Not solved yet, but has characteristics that make it potentially more complicated than anything I found in New York or other states.

Double usage of numerically identical voter ID numbers for different people, like “700388630” and “0700388630”. The leading zeroes technically differentiate them, but most programs ignore the first 0, making them identical in practical usage.

A previously undisclosed second ID number that happens to be encrypted. It is unknown at present why these were made, but their mere existence seems to violate the federal requirement that each voter is given a “unique identifier”. Two, it seems to me, is more than one, and thus not unique.

They do not provide any age-related information. This is unusual, though Wisconsin isn’t the only state that does this. Age information, especially Date of Birth (DOB), is very handy for confirming clones. Without it, matches on name alone are bound to include many false positives, making Wisconsin an ideal test case for the ‘common names’ hypothesis.

What is a “clone”?

One or more records assigned to a person who already has a record in the voter registration database. These are differentiated by ID number alone, or ID and other fields. I have seen every variety of this, from records that are identical except for the ID, to records that differ on ID, middle name, address, phone, and other fields, but still belong to the same person. This has been confirmed many times via canvassing.

What is a “Dup” or “Duplicate”?

A dup looks the same as a clone, except excess records share the same ID numbers.

Please note that I have received some strenuous resistance from people I respect to differentiating records this way. The complaint comes from associations between the word “clone” and science fiction. However, “clone” is a real word that has real meaning in modern science. It means “an independent copy”, such as voter registrations that can be used independently because they have different voter ID numbers. That is what I see in voter rolls, so that is what I intend to call them unless specifically instructed not to in specific contexts.

Despite Wisconsin’s lack of DOB data, we can still examine name frequency patterns to address a common objection to clone identification.

How are clones identified?

The easiest way is to create what is called a “match field” that combines name and age fields. For instance, “JOHNRSMITH19701225”, and then finding all records that match the match field. If more than one, check ID numbers. If different, you have a potential clone, otherwise, a duplicate. If you don’t have DOB, substitute something else, like Birth Year or age, which states provide instead of DOB.

Common misconceptions

Common names do not explain all matches, or even a majority of matches. This is the same principle as why a coin-flip lottery (1:2 chance) would have far more winners than one based on six 2-digit numbers (roughly 1:150,000,000). When you combine independent elements, the probabilities multiply. Getting both “John” and “Smith” together is much rarer than getting either one alone. Add a middle initial and full date of birth, and the chances of randomly selecting a specific match become vanishingly small - even for names we think of as “common.”

For reference, here are actual numbers from Wisconsin:

Total records: 7,744,986

“John”: 107,205 (1:72)

“Smith”: 45,796 (1:169)

“R.”: 493,122 (1:16)

“John R. Smith”: 42 (1:184,404)

At most, there can be 42 different DOB values possible for this name. All of the addresses, phone numbers, and emails are different except for one case: two records share the same email address but have different ID numbers, making this a confirmed clone. For this particular “common” name, there is one verified clone in the entire state of Wisconsin.

Paquette’s Law

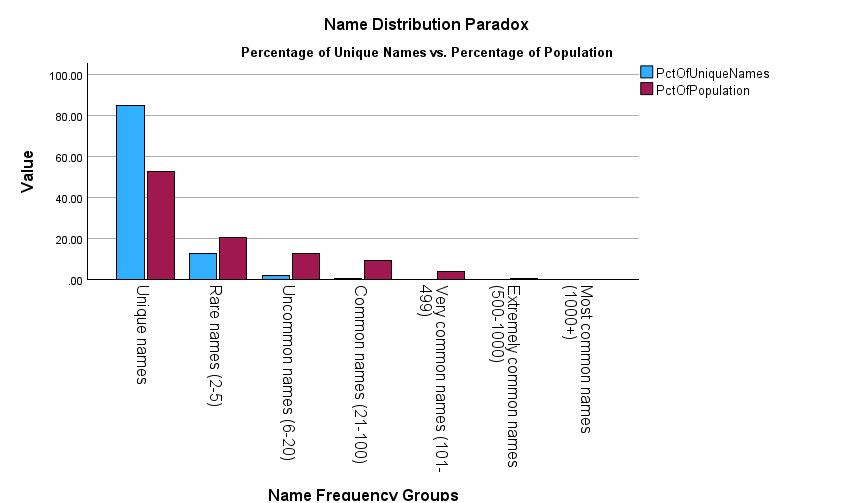

Paquette’s Law, which I’ve just made up here to claim some academic turf, is this: “Common names are rare and rare names are common”. This is the opposite of Zipf’s Law, which states that common words dominate in normal usage.

I’ve explored the mathematical basis for this in another post, so here I’ll focus on the empirical demonstration.

The Name Paradox

When I talk about cloned records, meaning multiple identification numbers assigned to the same person, critics often raise the issue of common names. They say that they aren’t true clones, but false positives. Some names are so common, they say, that we should expect that each state will have multiple people of the same name. This much is true. However,…

Common names, like Maria Rodriguez might occur over a thousand times in a database, but not many names are like Maria Rodriguez. In fact, the bulk of all names are unique, which is as rare as they can get. Therefore, the absolute number of records attached to all common names is significantly less than the number of records for rare names.

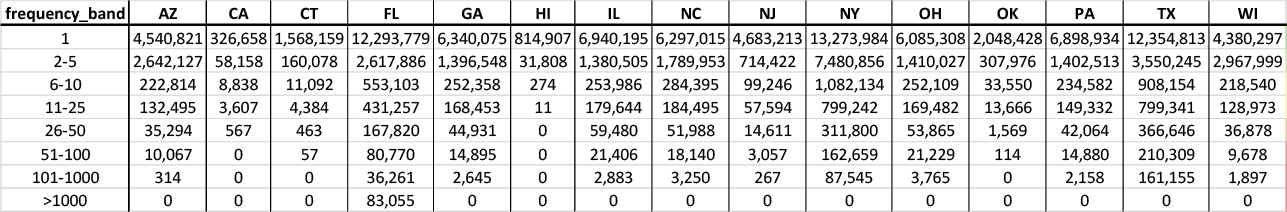

To perform a different analysis, I had to look through every state voter roll database I had. This incidentally created an opportunity to give a demonstration of Paquette’s Law. In the following image (Table 1) name frequencies are listed by quantity for each of the 15 state databases I have. They show quite clearly that unique names dominate every database, and common names are extremely rare. There is what appears to be a spike in Florida’s common names, but that is due to protected records that have blank name fields, making over 83,000 different people look like they have the same name.

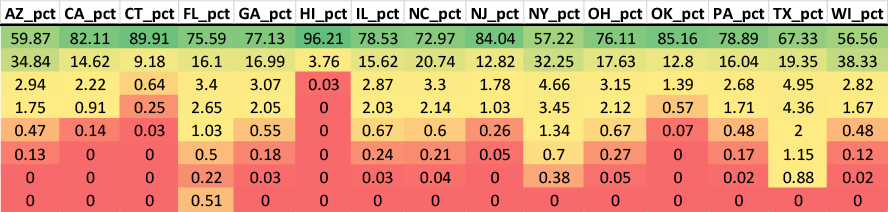

This might be easier to see as percentages, so here is a table to illustrate how rapidly records drop from rare to common names (Table 2), from an average around 70% unique, down to the low single digits by the 11-25 rarity band, which isn’t even close to the Maria Rodriguez level of common (1900 times in FL).

Conclusion

Paquette’s Law demonstrates a fundamental principle about identity databases: unique name combinations vastly outnumber repeated ones. Across 15 states containing 126 million voter registration records, an average of approximately 70% of full name combinations appear exactly once. Common names—those appearing dozens or hundreds of times—represent only a tiny fraction of total records, typically in the low single-digit percentages.

This has direct implications for clone identification. When critics argue that “common names naturally create duplicate matches,” they are making an empirically testable claim. If common names explain the clones found in a database, then the total number of clones cannot exceed the total number of records with common names. As we have seen, records in the “common name” frequency bands (appearing more than 25 times) represent a limited pool—less than 4% of all records combined (TX), 2% in NY, and less than 1% in every other state.

The question then becomes: How many clones actually exist in these databases? In the next post, I will demonstrate that the answer presents a mathematical impossibility for the “common names” hypothesis. The number of clones found in some states is so large that even if every single common name record in a state was a clone, the common names pool still could not account for what exists.

I like Paquette's Law!

Hi there. I have been actively involved in election fraud in CA. Are you working with a group or on your own? Would you like to work with other patriots? Thanks for all you do!🇺🇸