A few years ago, I knew a New Yorker, now deceased, who frequently asked me to send my findings out for “peer review.” What he meant by this is that he wanted me to send my findings to all those people I know who have PhDs so they can validate my work. Basically, send them to my friends so my friends can say their friend knows what he is doing.

That isn’t peer review.

“Peer review” doesn’t mean sending your work to people who know you (peers) so they can review your work. More often, it means removing all identifying information from a detailed technical paper you’ve written, and submitting it anonymously (with a tracking code) so reviewers who are experts in your domain can examine your work without bias. After it’s accepted, your name is restored to the paper, not before.

The goal of peer review is less about validating someone’s work than it is about ensuring the highest possible standard of research and accuracy. I have read about some wayward journals whose idea of peer review is to cash a check for publication, but I’ve never run into a journal like that myself. The journals I’ve published in take their jobs seriously. For one article, I had to redraft it so many times I lost count. The principal reviewer not only wanted my statistics to be accurate, he wanted the statistical argument I made to be as good as it could be, and that meant I had to do new research just to answer his questions.

The way it normally works, at least in my experience, is that you make a submission electronically by uploading your paper after you’ve done everything you can to ensure it meets the standards and format of the journal. Then you wait quite a while. I think the quickest first response I’ve ever received was a month later, but it is more often a several month wait before they acknowledge your material. The first reply comes with an email that says something like this:

“Thank you for your recent submission to the Journal of Exciting Things in Science. We cannot accept your article in its present form. However, our three reviewers have made some suggestions for how to improve your paper. Please read them and get back to us to let us know if you wish to continue with the submission process or go elsewhere with your article.”

At this moment, I have four papers out for peer review. Two are scheduled for imminent publication, I haven’t received comments yet on the third, and the fourth hasn’t been acknowledged yet after two months.

The beauty of peer review is that the reviewers or even the editor can catch what would otherwise be embarrassing errors before they get published. Not that it has ever happened to me (I think) before any of my articles have been published. I do know, however, that several of my papers have been improved considerably because they went through the process.

This weekend, something happened that reminded me why the peer review process is so useful and laudatory. Ironically, it was the form of “peer review” my recently deceased acquaintance once advocated so fervently, and not the real thing. I was going over my latest report on Wisconsin with a friend who happens to have a PhD, and he spotted what turned out to be a huge error. The python script I used to analyze the rolls had sorted the data in a way that caused it to compare the wrong lines of data. That led to the appearance of something rather shocking, which became the primary focus of my report.

So there I was on the phone with Dr. Jerome Corsi, and he said something like, “wait a minute, what about these two lines” as he indicated the mixed-up lines in question. I looked at them in horror as I realized that Dr. Corsi had identified a methodological flaw (the Python code) that had to be dealt with immediately.

I spent my Memorial Day rewriting my report after running additional analyses to determine whether the problem Dr. Corsi identified simply obscured a genuine phenomenon or revealed that the phenomenon was entirely an artifact of the methodology. Unfortunately, it proved to be the latter. This meant gutting the previous report and rewriting it almost from scratch—a process that kept me working until I finally sent it out at 3:53 AM (I initially estimated 4 AM, but decided to check my email for the precise time). This small moment of verification actually illustrates an important principle that my supervisors at King's College London emphasized repeatedly: when you know or can easily discover exact information, always use it rather than approximations. It's a simple habit that significantly strengthens research writing.

I’m writing this post as a reminder that second opinions can be very handy, and when you get them, it sometimes pays to check them out.

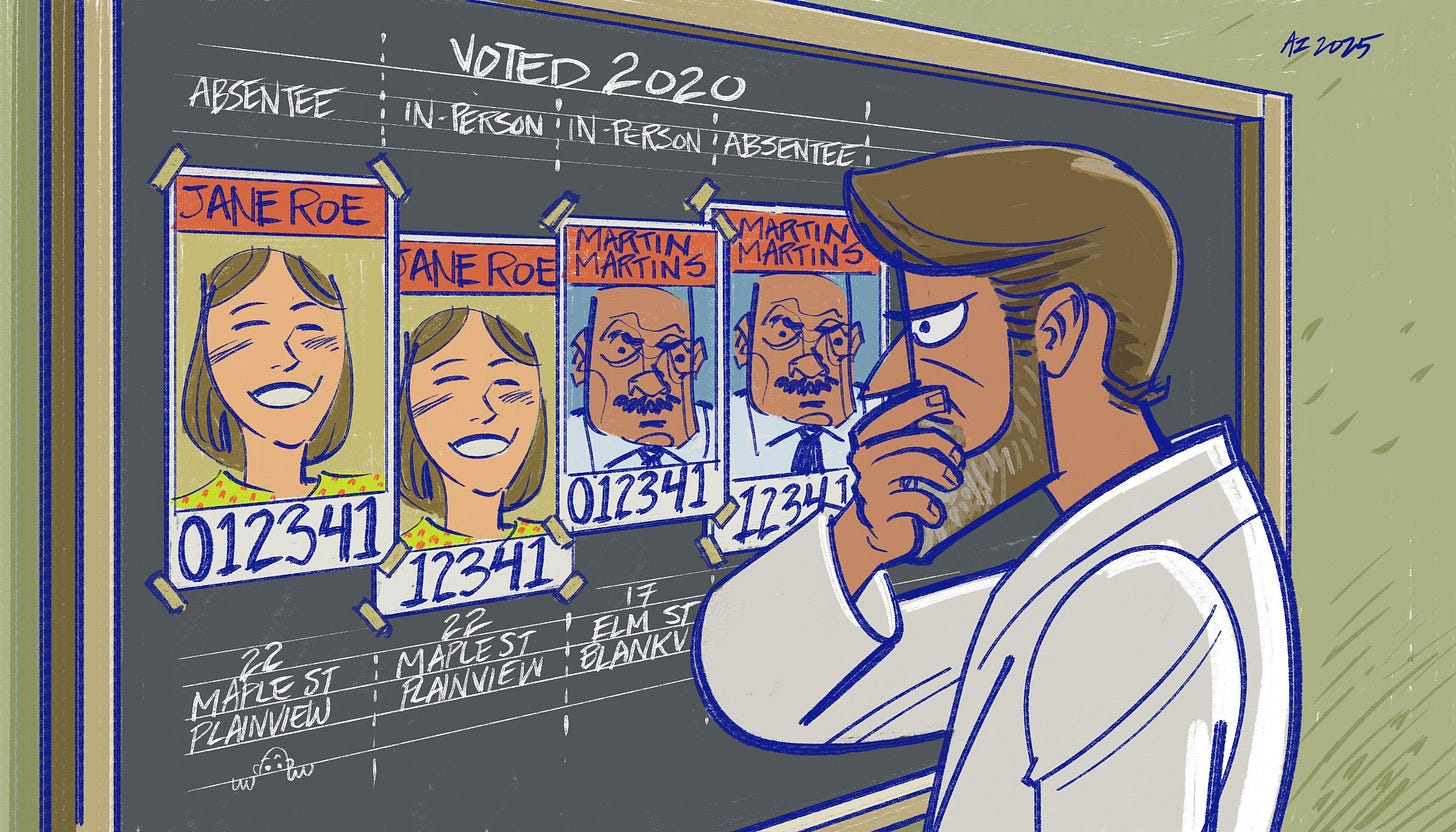

PS: The illustration for this article is what the data looked like until I learned of the Python error. After that, there was still a problem in the data, but it wasn’t anywhere near as shocking as it looked at first.

Thank you, for all you do.

(Wasn’t there some minor thing in a chart (one of those long “[ ]” accompanying illustrations) in the NY paper that got missed by everyone until after publication? (I think you caught it “live” during a subsequent Twitter space discussion you had on it.) Does this ring a bell?)

ps: Your work is excellent. We all have those moments that make sense at the time but then surprise us later after the final product has been released. I remember going over a regents math exam in my head afterwards and then recalling to my horror that because I had added 4 + 25 like that (and not with the 4 under the 5 like we usually write it) that I had got 30 instead of 29. My test score therefore was 98 instead of 100.

But I still remember it some 40+ years later.